Napa’s Wild Wines: Vineyard Microbiology

Winemaker Igor Sill enlightens about the wonders of wild yeast and how it is so important for making wine.

BY IGOR SILL via Marin Magazine

Fine wine is powerful. It touches you, inspires you, creates some of the most important memories in life and has the ability to move us, emotionally and physically.

I’ve always wanted to better understand the origins of that wonderful, warm feeling that overtakes me when I sip a glass of an exceptionally crafted red wine. Sure, the alcohol has a mind-altering euphoric affect. Wine is certainly one of the most universally enjoyed substances in history, dating back to the dawn of civilization. I have come to the realization that wine is truly a living thing, actually a microbiological organism, and there is convincing evidence that natural, wild indigenous yeast species serves as the very heart of fine wine.

My life as a vintner and winemaker is probably the most personally life and time-consuming of any business that I know of, and as much as I would like to tout my refined wine crafting skills and stewardship of vineyard nourishment, it is that magical living thing, wild indigenous yeast that does all the work in the creation of a fine wine.

Native, indigenous wild yeast, which surrounds the vineyards, pervades the world of wine. I’ve learned that the role of naturally occurring yeast is one of the most singularly important ingredient that gives birth to a fine wine. Turns out that we winemakers don’t actually create wine, the yeast and bacteria do.

There’s also an abundance of evidence that red wines grown at higher elevations possess greater levels of health benefits.

Yeast creates the wine, and the winemaker simply attempts to direct its character and style. What’s more, yeast produces more than just alcohol, they produce antioxidants along with numerous healthy nutrients including folic acid, B6, thiamine, niacin, riboflavin, all elements of vitamin B. Basically, the vines synthesize the antioxidant resveratrol as a response to natural UV sunlight. Resveratrol is a naturally occurring polyphenol antioxidant that is found in some plants, like grape vines. The phenolic content in wine can be separated into two groups, flavonoids and non-flavonoids. The non-flavonoids include the resveratrol and phenolic acids. These phenolic acids provide some of the most important elements in assessing a wine’s quality and are, very possibly, responsible for the beneficial health properties of red wines.

“Red wine has been demonstrated to have a beneficial effect on preventing heart disease. The mechanism of this benefit isn’t known yet, but we have been drinking wine for many centuries and, in addition to the joy it provides, scientists are working with vintners to better understand its health effects,” said Dr. David Agus, professor of Medicine & Engineering, University of Southern California. He is also an author of several books, including The End of Illness, A Short Guide to a Long Life” and The Lucky Years: How to Thrive in the Brave New World of Health.

Many winemakers use commercial monoclonal yeast to predictably ferment wine, but a number of boutique mountain-air vintners have kept the magic of native wild yeast while minimizing the use of those commercially altered yeast strains. I see commercial yeast as a counterfeit, an imitation to the “real deal”. To me, natural yeast is the soul and spirit of its native terroir and the most important element that differentiates a grape’s journey to becoming an exceptional wine.

Wild yeast is exactly what the name implies; it is the naturally existing yeast blowing and circulating in the vineyard’s air much as pollen does. The yeasts in vineyards seem to flow from wind-ruffled trees, transported by bees, and insects that surround the vineyard. Wild yeast attaches to surfaces of the grape skin and, as it hangs onto the skins, it faithfully represents its surroundings, the air, sunshine, temperature, bees, vines and many other elements. It’s a complex organism that fuels and drives many processes in the crafting of wine and certainly influences the final, finished product.

Napa’s volcanic Atlas Peak ridges, sitting between 1,200 and 2,200 feet in elevation, is the result of tectonic processes that formed the magic of its basaltic terroir, and a perfect setting for wild yeast. This high elevation moderates temperature extremes, allows for a longer growing season than the valley floor with an abundance of pure unadulterated clean air creating one of the finest locations for growing organic grapes in the world. This area is renowned for its superior Cabernet Sauvignon grapes swarming with a variety of native wild yeasts from the Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. cerevisiae), Candida, Pichia and sometimes Hansenula genera to drive the initial fermentation energy. Though a varied number of yeast strains help to get the fermentation process moving, S. cerevisiae is the dominant strain that does the heavy lifting in virtually all wine fermentations.

Wine is truly a living thing.

Fermentation is a complex biochemical reaction in which yeast consumes sugar in the grape juice (must) and releases alcohol and carbon dioxide. It determines the future quality of wine and occurs shortly after harvest. Fermentation can take anywhere from four to eight days for red Bordeaux-style wines, and as long as several months for Burgundian-styled white wines. We have the Frenchman Louis Pasteur to thank for discovering yeast’s role in the microbiological fermentation process (August 1857). “He showed us that fermentation was due to life, thereby confirming an instinctive and almost universal belief that wine was not a mere chemical concoction, but a mysterious living organism, divinely appointed as the symbol of life,” states renowned Biochemist Dr. Sondra Barrett. Today we continue to research, explore and learn from Pasteur’s many wonderful discoveries.

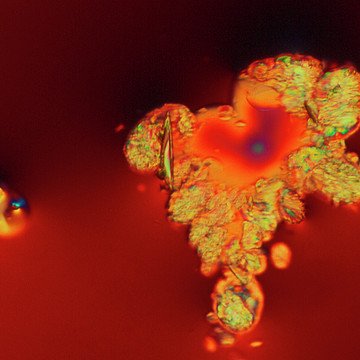

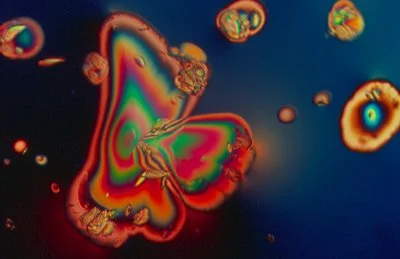

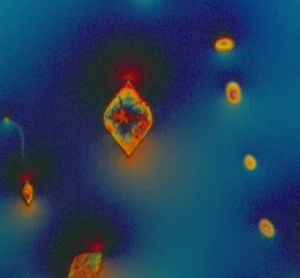

Dr. Barrett is also a medical scientist who researched, with a microscope, the development and maturation of normal human white blood cells to improve diagnosis and follow-up of leukemias (cancer of white blood cells). Seeing a surprisingly beautiful exhibit of chemicals of the brain, she began photographing through the microscope vitamins, minerals, hormones, flowers, herbs, and finally got to wine, finding that beautiful stuff of life was part of each of them. It was when she was artist-in-residence for Sterling Vineyards in 1984 that she got bitten by the wine bug. Working independently and with Napa Valley winemakers, she uncovered visual evidence that wine evolves. Through the microscope, wine’s must reveals tiny simple geometric forms and as wine ages, those forms become larger and more complex.

She asserts that you can also see when a wine begins to lose vitality. The beautiful expressions in the wine can no longer refract light and visually falls apart. That wine is living and evolving can be seen in the images displayed here. As Dr. Barrett interprets the images, the wine at 2-years-old was very focused; another year later it opened up and mellowed. For those of us who enjoy fine wines and are curious as to why a Cabernet Sauvignon may improve with age, or another bottle opened yesterday has completely fallen apart, her photomicrographs of changes in wine as it evolves into different energetic expressions are fascinating clues. “I am sure these microscopic portraits of wine’s inner structure tell us something about the wine’s character and inner nature – for beauty of how a fine wine evolves,” she says. “It’s really about the art of the science.”

Renowned Napa enologist, Derek Irwin states: “The reason why I am a big fan of starting off with indigenous wild yeast is that wines should reflect the natural taste and characteristics of the place where the grapes are grown. They respond to their natural stimulus from their terroir and as such need to breathe, evolve and transform the grape’s sugars gracefully into fine wines as they surrender their lives as a matter of organic chemistry versus commercially augmented programming. I find that wines that have had an indigenous wild start tend to have more complexity, flavors, texture and elegance to them.”

Adding to the benefits of indigenous yeast, the addition of rhythmic music introduced during the yeast’s gestation period interacts with the microorganisms and enlightens their magical elements, truly bringing them to life. I believe that this increased yeast activity translates into fuller-bodied wines with a deeper complexity of flavors. When I drink the wine, I can sense and taste the effects of playing Chopin, Borodin, Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue”, Ravel’s “Bolero” and even Barry White’s “Can’t Get Enough of Your Love” on the wine’s development. The systematic arrangement of these rhythms stimulate perfection of elegant construction, exquisite detail and harmony which propels the yeasts’ passion for their tasks, converting sugar into alcohol. Serenading the yeast’s activities encourages far better single-cell conversion involvement in our fermentation tanks. The rhythmic vibration and harmonious sounds seem to maintain a much more constant fermentation temperature allowing our wines to truly ‘open up’ with a depth of flavor, aromas and complexity that you really savor because the experience of the whole is more than the sum of its parts.

As in art, music, science, health and life, the simplest of details can bear extraordinarily exceptional results.

Igor Sill

Igor Sill precision farms a sustainable eco-friendly volcanic mountain vineyard on Napa’s Atlas Peak Mountain, Sill Family Vineyards. He’s a passionate wine lover, winemaker, and writer. He is a member of the Court of Master Sommeliers, the Napa Valley Wine Technical Group, a judge for the International Wine Challenge in London, holds his master’s from Oxford University and attended UC Davis’ winemaking program. He thanks Dr. David Agus, Dr. Sondra Barrett, and Derek Irwin for their much appreciated assistance, insights and contributions to this article.